2.5 Peatland Complexes

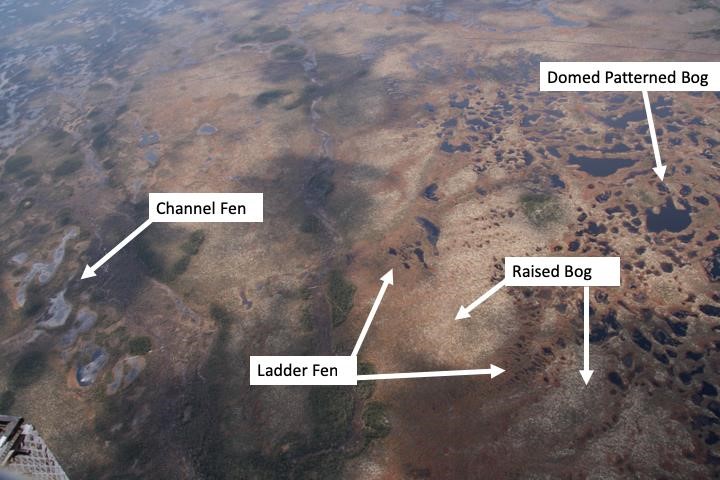

Over the long term, peat accumulation and the associated rise in water table elevation saturates adjacent areas so the peatlands can expand laterally, depending on local topographic gradients. Where climate is suitable, and Quaternary sediments are relatively flat and of sufficiently low permeability (Glaser et al., 2006), peatland complexes such as those in the Hudson Bay Lowland and Glacial Lake Agassiz area can develop. Peatland complexes like these host an assortment of bogs, fens, and swamps that dominate the landcover, coalescing as the peatlands develop. Over time, peat accumulation and system development alter the class of peatland and patterns of connectivity. Sometimes, flows from large bogs self-organize and drain through narrow fen systems (Figure 7), which often form into patterns of ridges and flarks (e.g., ladder fen, ribbed fen; NWWG, 1997). While bogs can also generate ribs and pools, the less distinct hydraulic gradients result in a disorganized pattern of pools/ponds on the top of the dome (Price, 1994). This is visible on the domed bog in Figure 7.

Figure 7 – Peatland complexes are assemblages of individual peatlands, where local hydrological and topographical gradients drive the exchange of water and nutrients among them. Here, a peatland complex in the James Bay Lowland has a large domed bog occupying the highest local elevation. It drains through ladder fens on its flanks and eventually to a large channel fen that comprises part of the regional flow system. Smaller raised bogs occur in interfluvial locations, including between adjacent ladder fens. (Photograph by J. Price)