6.2 Groundwater in Karst Settings

With carbonate bedrock forming about 15% of Earth’s ice-free surface as shown in Figure 41, more than 25% of the world’s population either lives on, or obtains its water from, karst aquifers.

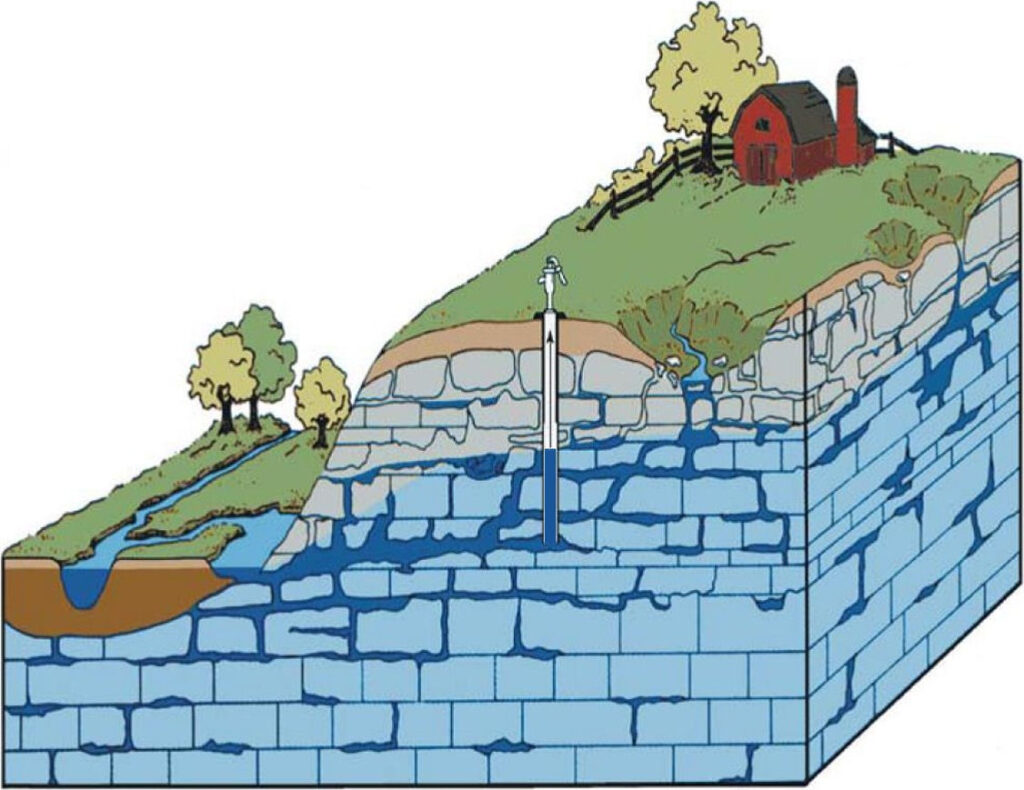

Karst aquifers consist of large openings in the subsurface connected by caves and sinkholes (features where the land surface overlying a cave has collapsed into the cave) as illustrated in Figure 42. They are formed over geologic time scales by acidic water in the vadose zone dissolving substantial amounts of the minerals in limestone and dolomite that groundwater carries away. Later, the process of creating openings in the subsurface is halted as the dissolved minerals neutralize the acidity of the water and the water loses its capacity to further enlarge flow paths. Subsequently, when climate becomes more arid and/or sea level falls, the water table declines, and the acidic infiltration water creates additional caverns at deeper levels. During wetter periods and/or when sea levels rise, the caverns fill with water creating a saturated karst aquifer. Fluctuating water tables over geologic time produced deep karst aquifers in many locales throughout the world.

Recharge water flows more rapidly through connected karst openings to discharge at springs and streams than through other types of sedimentary aquifers. Given the large connected openings of karst, groundwater flow is more similar to flow in streams than to flow in sediments or fractured rock. Finding sufficient supply of surface water is often difficult in karst terrains because water infiltrates rapidly. The rapid movement of water through karst aquifers makes them prone to extensive contamination.

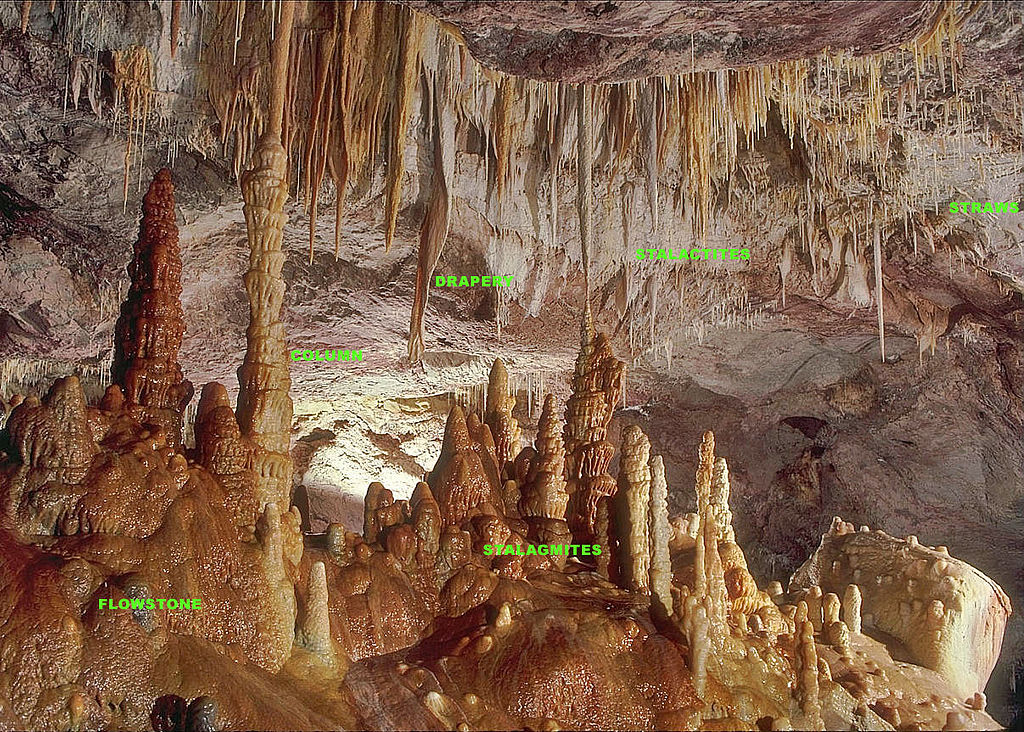

Karst is the only landscape where humans can explore large distances into the subsurface on foot through dry connected caves or using scuba gear in water‑filled caves. In addition to their value for water supply, they support tourism where majestic caverns are adorned with mineral “jewelry” of cones and columns that are formed when the groundwater contains more minerals than it can carry and the minerals precipitate from the water (Figure 43).